Marketing is about creating and executing strategies, and there are several, connected strategies in a strategic plan. The marketing strategy helps make sense of all the strands of a brand’s strategic plan, but it is also the strategy many marketers (and instructors) struggle with. In this article I discuss two real-life marketing strategies – one weak and the other strong – both from giant brands. Then I discuss how to create a marketing strategy that delivers what it promises.

This is a rather long article. I suggest you print it and read it when you have time. You might find it not only interesting but also very useful for your job. Stay with me.

Serious marketing requires professional marketers

Take a look at the Flowmeter market in the process automation industry. All brands[1] are struggling to identify a unique benefit for their brand. Read Table 1, they all say I measure flow accurately, I am accurate and reliable, I give precise measurement, I am highly accurate, and so on.

| Company | Brand’s reason to buy |

| MicroMotion (Emerson) | Unmatched flow and density measurement |

| Endress+Hauser | Premium accuracy, robustness and extended transmitter functionality |

| Yokogawa | Accurate and stable flow measurement |

| Siemens | Versatile and reliable metering solutions |

| ABB | Precise measurement of mass flow, volume, density |

| Krohne | Cost effective solution for accurate measurement |

| Oval | Directly measuring mass flow with high accuracy |

| GE/Reonik | Highly accurate measurement |

| Foxboro/Invensys (before 2014) |

We handle measurements that cause other coriolis meters to fail This was the only claim in this list worth mentioning. Then Schneider Electric bought Foxboro/Invensys in 2014. Read their new claim in the next row. |

| Schneider Electric (ex Foxboro/Invensys) |

Accurate, reliable and worry-free flowmeter solutions |

Table 1: Product (pseudo-)benefits of major flowmeter brands.

Do you know what happened? Customers had no reason to prefer one flowmeter over another, so for a decade or two, established players competed on price, giving discounts of 40%, 50%, or more. Then a few years ago no-frills, low-cost flowmeters hit the market and all the old-time products began losing market share.

Product technical performance isn’t a benefit that differentiates between competitors and wins the preference of customers. It is just the pre-requisite to enter the market. You must creatively translate it into a real, unique and desired benefit, or your brand won’t be around for long. But by “creatively” I don’t mean the creativity of a graphic designer or an advertising person; I am talking about strategy and not design.

Framing the marketing strategy

The Marketing Strategy is created according to three principles: (1) It must satisfy an important consumer need, (2) it must be very specific and clear, and (3) it must be distinctive in the eyes of consumers. It is made of two parts[2]:

- Overall marketing objective: What the brand is supposed to achieve.

- Positioning statement: How to achieve the marketing objective.

Forget for a moment your brand’s particular situation. Creating a marketing strategy that delivers what it promises follows a pattern applicable to any brand, in any market, at any development stage. Whether your brand creates a completely new market or it joins an existing, crowded playing field, you always follow the same approach to create the marketing strategy.

Before we dig into how to create it, however, let’s look at the marketing strategies of two giant brands: one is a weak marketing strategy and the other is strong.

Example of a weak marketing strategy

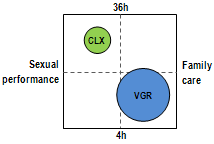

In 1997, Pfizer launched Sildenafil, a breakthrough drug that in a matter of months opened a new, large and profitable market. Marketed under the brand name Viagra (VGR), Sildenafil did great business until 2004 when Tadalafil (Cialis, CLX) hit the market, and in less than 24 months moved one half of sales value away from VGR. Both are erectile dysfunction drugs (EDD), they are comparably effective and safe, VGR takes effect more quickly and CLX lasts longer, their prices are alike, and they have similar levels of marketing support.

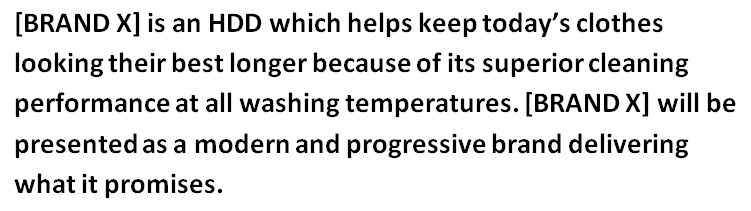

At the beginning VGR’s marketing strategy read:

Image 1: Example of a weak marketing strategy.

CLX entered the market with just one major claim – We last longer – claiming 36-hour efficacy as opposed to VGR’s 4-hours.

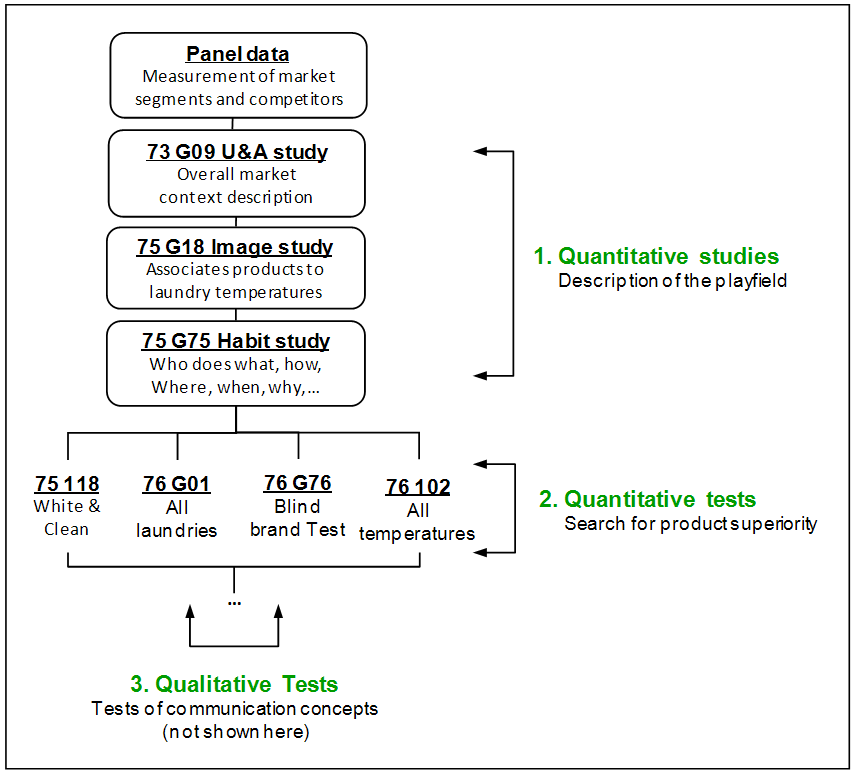

When VGR realized they were losing share the brand management added a sentence to the marketing strategy, which became:

Image 2: Example of an even weaker marketing strategy.

What went wrong with VGR? Why did VGR lose the market it created? Because it was built upon weak strategic directions. It wasn’t clear who they were speaking to and why customers should prefer VGR to CLX.

Although Pfizer’s product satisfied an important need, they failed to create a specific and distinctive strategic claim. So Pfizer lost the advantage of being the first in the market, and lost market control after achieving an almost monopolistic market share position.

In short, Pfizer didn’t think strategically.

Anatomy of a bad marketing strategy

VGR failed to maintain their advantage because they didn’t identify the real benefit they offered to customers. And it wasn’t just treating erectile dysfunction (ED). Treating ED was just the pre-requisite to enter the market.

Read Image 1 again. The unsurpassable efficacy claim is strong. What’s not clear and made the strategy weak is:

- What the overall marketing goal was. What is this strategy supposed to achieve? If you don’t know where you are going chances are you will never get there.

- What a first quality erection is.

- How long is long enough and for what is it enough?

- What the customer’s real need is.

- Who the customer is.

Written this way the marketing strategy doesn’t allow a consistent execution. In fact, as soon as a strong competitor entered the playground Pfizer changed their strategy. That was a lethal sin; leaders should never follow their challengers, but Pfizer did. By saying We want to replace Tadalafil, Pfizer were admitting they didn’t know how to counter a tough competitor (I hope my colleagues at Pfizer won’t mind this last sentence) and reversing their position wasn’t the right move. Followers and challengers try to replace leaders, and not the other way around. Moreover, what happens if for some reason, for instance due to safety issues, the competitor is withdrawn from the market? Do we change the strategy again? Wrong!

Strategies are created for the long-term.

The mistake, however, was made much earlier, at the time Pfizer launched the product. They didn’t anticipate how the market might evolve over time and they didn’t shape their strategy accordingly. A consumer goods (CG) company of the same caliber as Pfizer wouldn’t have made the same mistake, but Pfizer isn’t a CG company, and at that time pharmaceutical companies were still learning how to deal with the so-called lifestyle drugs. So I’d excuse them.

Learning strategy from the original

Comparing a bad and a good strategy makes the differences clear, and makes it easier to understand how to create strategies that deliver what they promise.

There is only one company to learn strategic marketing from: Procter & Gamble.

The overall brand objective is inspired by the company’s Statement of Purpose. It should be clear and measurable, but without referring to any figures or quantities; and it should be achievable, but not too easily. Image 3 shows the overall marketing objective of [BRAND X].

Image 3: Overall marketing objective of [BRAND X].

This objective inspires the product strategy:

Image 4: Product strategy of [BRAND X].

The product strategy contributes to shape the positioning statement:

Image 5: Positioning statement of [BRAND X].

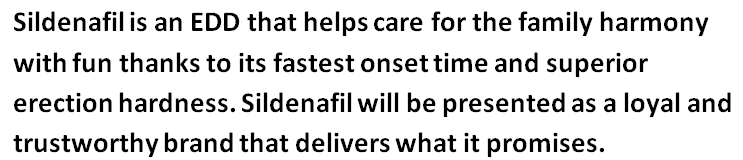

The logic is straightforward. The marketing objective was market leadership. Management defined the product characteristics deemed necessary to achieve the objective. The positioning statement translated what the product does into what the customer gets. The whole process was justified by a multifaceted marketing research plan as shown in Image 6.

If you don’t research, you guess. If you guess, you don’t yet know. Real marketers do professional research to make sure their guesses are right.

Image 6: Marketing research plan to support the strategies of [BRAND X].

There is however an anomaly in the positioning statement in image 5 that cannot be supported with market data: How can a wash detergent justify the claim keep today’s clothes looking their best longer?

The strategic logic of the positioning statement

When do clothes look their best? When they are new and clean.

[BRAND X] cleaning superiority is supported with evidence from lab tests. The challenge is how to support the claim Clothes look their best longer. How can one prove an HDD is delicate with fabrics and strong against dirt?

The answer came from the lab: Adding Builders to the product formulation justifies the claim. This is marketing creativity and it shouldn’t be confused with the creativity of art directors and graphic designers.

Builders lower water hardness by scavenging calcium and magnesium. These minerals act like stones during the wash. They scratch the fabric, which begins to deteriorate. Scavenging the stones the friction is gentler, and clothes last longer. Less hard water is less aggressive on fabrics, which indeed, thanks to [BRAND X] new formula, can now Look their best longer than clothes washed with other brands. This is a logical and strong benefit (make sure consumers agree). It’s unique to [BRAND X], it’s not easy to copy, and it’s important to consumers, who in fact soon elected [BRAND X] to market leader, a position it still holds.

Looking at the product composition through a marketer’s eyes may suggest new product ideas worth testing. Although the example in Table 2 refers to an HDD, the concept can be easily transferred to any other product.

| Magic Ingredient | Action | Benefit |

| Surfactants | Lift dirt from clothes | Clean clothes |

| Builders | Lower water hardness | Clothes looking their best |

| Brighteners | Offset yellowing | Wash whiter than white |

| Bleach (mainly US) | Removes stains | Clean at low temp (<40°) |

| Bleach (mainly EU) | Removes stains | Clean at high temp (>60°) |

| Catalysts (mainly EU) | Boost the bleach effect | Clean at low temp (<40°) |

| Enzymes | Remove stains | Clean at low temp, faster |

| Sodium silicate | Inhibits corrosion | Washing machine lasts longer |

| Anti-foaming agents | Low foam production | Fast wash & clean environment |

| Conditioner | Fabric softener | Softer fabric |

| Alcohol | Dilutes ingredients | Highly soluble |

Table 2: Ingredients of an HDD.

If we know what the product does and how it does it, we can find ways to improve its performance to increase customer acceptance by making the product superior and unique[3].

There are two more things worth discussing from Image 5: the all washing temperatures and the modern and progressive brand claims.

Positioning is built upon segmentation and differentiation

Segmenting the market is vital to set a clear and credible strategic direction for the brand.

Think again of Sildenafil: they didn’t set a major market segment they aimed to conquer and defend. [BRAND X] on the other hand chose to appeal to people who could identify with a modern and progressive brand, about one-half of the market. The other half was composed of traditional and conservative people.

In our marketing strategy we want to define a clear market segment to conquer, because then we can speak a language that appeals the members of the group, and this sets the conditions for the brand to win their preference too. Speaking in generic terms of the customer doesn’t help to focus the message and chances are we will waste resources on the wrong audience. And if we are good enough we may find a market position that leaves little room for competitors to attack us.

Like Sildenafil, if we don’t have a target segment, when the market splits (and sooner or later all markets split with the entry of new competitors[4]) we may lose direction and begin running back to challenging competitors. At that point we are caught and our brand is destined to fail.

How would you have positioned VGR to make it an enduring success?

Keep reading – I’ll soon tell you what I did.

Some managers argue that they do not split the market in order to not lose potential customers. Well, setting a clear target to speak to doesn’t imply others won’t hear what we communicate and, with regard to our example, even traditional and conservative people may try our product. Moreover, if we do not split the market, the market will do it for us, and all of a sudden we may find our brand pushed out of the playing field. If we do segment the market, however, and choose to win in one segment, when the time comes and a new competitor challenges us, we will have built awareness and hopefully loyalty, which will enable us to defend our brand effectively and with a purpose.

Marketing research helps building brands that deliver what they promise

“I think…” isn’t the way to deal with strategy. “Facts and data suggest…” is the approach to prefer, and the data comes from marketing research.

Back to the research plan of [BRAND X] in Image 6: panel data is important for measuring market segments (and competitors) in volume, value, and tendency.

The voice of the customer is all important, and we need studies and tests to create sound marketing strategies.

Studies are broad surveys conducted less frequently than tests, say every 1-2 years. For our purpose we begin with a Usage & Attitude study (U&A), to get a panoramic view of the context our brand will compete in. As the name suggests, this kind of study investigates how customers use products of the category we are interested in, and what they think or feel (attitude) about the existing brands.

This first study may help, among other things, to identify direct competitors that we can investigate further with an Image study, to learn what products customers associate with different usage conditions. For instance, if we sell snacks, which brands associate with breakfast and which with afternoon breaks? If we sell shoes, which associate with sport activities and which with leisure? And so on. In the case of [BRAND X] it was washing temperatures.

Thereafter we conduct a Habit study to understand who (customers) does what, when, where, why, and how when they use products of the category under investigation. Surveys investigating sexual and political topics may require some caution when planning the research, but they are doable too.

At this point we know:

- How the market splits according to product usage conditions

- What products are representative of which segments of consumption

- How customers consume the products

With this information we can identify market segments where winning customer preference may end up being strategically attractive and profitable.

Read this too:

How to go from data to information to insights and unleash the power of strategic thinking

How to create the product your brand deserves

Now it’s time to make sure we have the right product for the job, and this requires conducting tests.

Tests are dynamic surveys focused on single issues. The tests in our case are conducted mainly around the product technical performance, and we need several of them.

In the 1980’s, at the time I did research for P&G, brands like Dash (launched in 1954), MrClean (’58), ACE (’60), Pampers (’61), Oil of Olay (acquired in 1985), and others, even if they had been launched decades before, were still doing hundreds of tests on technical performance as well as various strategic and executive elements of communication. Why? Because brands can’t stand still. Improving product performance requires listening to the voice of the customer, and tests are the tools of choice. There are two kinds:

- Lab tests are conducted in-house by our research staff who measure our product against competitors

- Field tests are conducted in the market with customers

What do we test? The product at work!

[BRAND X], for instance, tested:

- White & Clean. We test this first in the lab, on its own and against major competitors and specialist brands. Does our product perform as it should? If not, go back to development and improve it. Then we test it in the field. Do customers perceive our product’s superiority (or equality)? If not, go back to development and improve the product.

- All laundries. Does the product deliver with both white and colored clothes? With both delicate and synthetic fabrics? With and without bleach? With and without conditioner? And so on.

- Temperatures. Does the product deliver at boilwash? At 60°C? 30°C? 15°C? And so on.

- Blind and identified tests. Perception may play a big role with customers. What happens when customers know the product’s brand name? In a blind taste test Coke and Pepsi performed equally well[5]. When the brand was disclosed, however, respondents preferred Coke significantly more (from a statistical point of view) to Pepsi.

Yes, professional strategic marketing requires more, much more than just saying “I think…” But what about when we do not have the budget to do the work as the professionals do? Two options: (1) Be creative and find ways to gather solid data on your own; and (2) Seek help from low-cost professional agencies like MarketingStat.

Differentiating products

The key question is “What makes our product different?”

The technical performance? No, that’s not enough to win big, and this was VGR’s mistake. In fact, as soon as a new, qualified competitor hit the market, VGR lost the market they created. On the other hand [BRAND X] has existed and continued to lead for over half a century. Why? Because they built a unique benefit based on technical performance and that is: Clothes look their best longer. Clothes washed with [BRAND X] are not simply clean or cleaner. That’s not a unique benefit. Washing clean is just the pre-requisite to enter the game. After all, if a heavy duty detergent doesn’t wash clean what does it do? If flowmeters don’t measure flow accurately what do they do? If VGR doesn’t guarantee an erection what does it do?

A better marketing strategy for Sildenafil

One day my boss, the Head of Pharmaceuticals at Pfizer, wrote me a single line email: Why is Viagra losing market share?

My answer was brief: “I think… I think I need data to tell you”. A couple of days later I sent a memo back. The issue was clear. Tadalafil had a strong claim (36 hours efficacy) and they executed it effectively (they won over specialist doctors, each of whom generated 10x more prescriptions than general practitioners, the group that Pfizer focused on).

My boss called a meeting inviting the Marketing Director, the Brand Manager, and me to discuss how to recoup the situation. I suggested repositioning Tadalafil in a negative area of customer perception.

The concept was easy:

Forget talking about the product’s technical performance (4 hours efficacy). Let’s speak to the heart of the couple. At that time two-thirds of EDD consumers were 55 years old and up, 80% were married, and one-half made purchase decisions together with their partner. We had to help these people maintain (or reclaim) the harmony of their partnership. Let’s help them care for their relationship. And four hours efficacy is long enough (now that makes sense). At the same time let’s question the need for 36 hours of efficacy. Who needs that? Someone who wants to show off their performance, perhaps outside of their marriage? Unfaithful partners? Egoists? That’s not our group. We should speak to those who care for their partner and their relationship: altruistic, trustworthy men who want to please their partner and enjoy a life of harmony.

Do customers (both partner and product user) accept the concept? Great, let’s rewrite Sildenafil’s marketing strategy:

Image 7: A better marketing strategy for Sildenafil.

Visually speaking, Sildenafil’s strategic positioning can be seen in Image 8.

Image 8: Strategic mapping of the EDD market.

Then it became a matter of strategy execution and communication. Only when the strategy is clear and solid we can create stories (story telling seems to be the buzz of the day) and all the content we like. But when we don’t know where we are going, chances are we’ll never get there.

And again, marketing is about creating and executing strategies. Test it all before you execute.

Closing on creating marketing strategies

I close this article with some nuggets of common sense mostly borrowed from Charles Decker. I hope you can link them back to what’s written above.

-

- Carve your space. But beware of I-Thinkers. Opinions don’t count.

- Trust the consumer

- Find the action in the data

- Split or aggregate the market

- Build superior products. But beware of strategic blindness. Pampers suffered from it in the 1980’s and lost significant market share to Huggies. Why? Because they got stuck on improving product technical performance when customers were happy with it but wanted more. They wanted product design, one of the three pivotal elements of the product strategy.

- Err on the side of technology

- The best is never good enough

- Create unique brands. Ed Harness, former P&G CEO, said: It is not enough to invent a new product. The real payoff is to manage that brand with such loving care that it continues to thrive year after year in a changing environment.

- Be your own best enemy

- Expand the benefit without compromising the brand

- Consumers buy products, but they prefer brands

- Relentless, consistent execution. But beware of sales blindness. There is no room left in the cemetery of market share buyers. Create and sell value and you’ll live forever.

- Brands can’t stand still

- Think long-term

- Think profit

- Learn how to write to learn how to think. Strategies are short statements, and writing briefly without missing any important elements is difficult. Thomas Jefferson once wrote to a friend“… I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one”.

Thank you for reading.

I’d be grateful if you would post this article to your social network.

[1] I use the words product and brand to mean both physical products and services.

[2] Procter & Gamble have recently begun using an extra element called “Brand Purpose”. I’ll discuss this topic in a separate post.

[3] For brands without benefit and support, such as fragrances, the approach is somewhat different. I’ll discuss this case in a separate post.

[4] Hint: Watch the Voice Controlled Speakers market as it is evolving. It is just beginning to split.

[5] Read: Neural correlates of behavioral preference for culturally familiar drinks. Neuron, Vol. 44, 379-387, October 14, 2004.